I always knew I wanted to have babies. I didn’t know, after several toxic relationships in my twenties, if I’d ever want to get married, but I knew I wanted to be a mother.

Right before I turned 28, I met an incredible man who was—and is—everything I hoped for in a partner. We got married less than a year after meeting—it felt right. We were best friends, excited to share our lives—the good, the bad, the devastating. And, five years later, we have—though I think we have had more than our fair share of devastation, having had to make excruciatingly difficult choices, without much support from the outside world, in order to bring our child into the world.

Trying to get pregnant

We tried to get pregnant for four years without success. For two years we tried “naturally.” One thing people don’t tell you is that trying to get pregnant, when it’s proving difficult, is anything but romantic—but it does create a new kind of intimacy. We are closer now than we’ve ever been.

They were clumps of genetic material that failed to continue to grow—but I felt like I had failed: myself, my husband, the children I dreamed of.

After these two years we consulted a fertility specialist. We then tried medically assisted intrauterine insemination (IUI)—six times. None were successful. Our next option was in-vitro fertilization (IVF), which is more invasive and complicated (and expensive). After two canceled cycles, we finally had an egg retrieval: 28 eggs retrieved, and 14 were mature and fertilized by intracytoplasmic sperm injection. By day five, we learned that none of our blastocysts—the cells created from sperm and egg—had survived.

It was a huge loss. It didn’t matter that the blasts weren’t actual babies. They weren’t even fetuses. They were clumps of genetic material that failed to continue to grow—but I felt like I had failed: myself, my husband, the children I dreamed of. It was my fault—well, my eggs’ fault. Problems that occur after day five are considered issues from the sperm. Before day three, it’s a problem from the eggs. And I blamed myself: Maybe it had been my diet. Maybe I drank too much when I was younger. Maybe this was some sort of sign from the universe that I didn’t deserve to have children.

After all this, when it came down to brass tacks, we were left with three options to have children: embryo adoption (adopting embryos already made from a sperm and egg; rough cost: $18,000 plus medication); egg adoption (adopting eggs and using my partner’s sperm to fertilize them; rough cost: $40,000 plus medication); or traditional adoption (adopting an existing child, but with no guarantee on a time or even a placement; rough cost: anywhere between $3,000 and $60,000—or more).

This is an incredibly personal—and stressful—choice. Different options are right for different people. None is right or wrong (and shame on people who pretend they know what they’d do without going through this situation—my husband and I sure didn’t until we were confronted with the very real choice).

Faced with our three choices, we chose embryo adoption—our baby would not be genetically ours, but I would carry and give birth to it.

When we made this decision, our infertility journey had cost over $80,000 so far. Insurance didn’t cover a thing.

Getting good news—and then bad

We carefully chose our embryos from a selection through our clinic. Our doctor agreed to transfer two, since I had never been pregnant before and my chances of conceiving naturally were practically zero. We signed paperwork acknowledging that the chances of having a singleton (one baby) were 60–80 percent. Twins were about 40 percent. The chance of those embryos dividing into triplets? Less than 2 percent.

I felt good about those odds—especially after four years of zero babies.

Four days after the embryos were transferred, I peed on one of many, many sticks. Finally, I saw what I had been dreaming of for years: Two. Pink. Lines.

At six weeks, we had our first ultrasound: twins. Two babies!??! After all these years of no babies!??! My husband and I were ecstatic. At first, the doctor thought she saw three, but she brushed it off as a glitch in the image. We left the office happy and excited to be parents to twins.

I was devastated. I felt cheated. I had done so much—physically, mentally, emotionally, financially—to have these babies and now I had to lose two?

A few weeks later, I experienced some minor bleeding, which is very common in the first trimester. We went for another ultrasound.

This time, the doctor’s face fell as the image came up on the monitor. It looked like she had just drunk bad milk: “You’ve got three in there.”

We knew, instinctively, that this was not good news—risky, at best, downright disastrous at worst. Later we learned that since the twins were sharing a sac, there was already a 40 percent chance of severe disabilities or death, which only increased with other complications I experienced.

Our excitement quickly turned to fear (not helped by the doctor’s reaction). I started to cry. My husband’s face turned white.

We were assigned to see a maternal fetal medicine specialist (MFM), a doctor with advanced training in complicated pregnancies. Our regular obstetrician told us this was “above her pay grade.”

Making (more) impossible choices

We saw the MFM about a week later. I was nine weeks pregnant at this point. I had another ultrasound. We saw all three of our babies on the big monitor, moving tiny arms and legs. I was already starting to show a little bump. In our meeting with the MFM, we were informed that our babies were a set of monochorionic twins—sharing a placenta—and a singleton, and one of the twins was already a week behind, growth-wise.

We were guaranteed preterm labor (we’d be lucky to make it to 30 weeks), and we were informed of the many, many risks of trying to carry these three babies to term. These ran the gamut from a 40 percent chance of all or some of the babies having profound birth defects to twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence (TRAP sequence), where one twin is developmentally normal while the other develops without a functioning heart and many other structures (head, limbs, etc.) that would allow this twin to develop into a normal fetus and newborn; possible lifelong health issues like cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, and vision and hearing loss; increased risk of stillbirth; increased risk of miscarriage; and the possibility that if one baby passed in the womb, they’d all go.

These risks exist with twin pregnancies, which are themselves considered risky. With a third occupant in the womb, the risks are even higher.

Multifetal, or selective, reduction was recommended by this doctor. And the next we saw. And the next. Multifetal reduction lowers the number of fetuses in the womb and increases the chance you will have a healthy continuing pregnancy. It’s an extremely safe procedure for the mother, and chances of problems for the remaining fetuses or fetus are very small. We saw the best doctors in the New York City area, and for all of them it was never even a question: Reduction was the only safe choice.

We had gone through so much to have these babies, and, so quickly, they were gone.

I was devastated. I felt cheated. I had done so much—physically, mentally, emotionally, financially—to have these babies and now I had to lose two? I had never even heard of multifetal reduction. I was desperate for support from people who’d gone through a similar experience, so I posted in online groups, but the responses I received were much different from the doctors’: “How could you even think of reducing?” “These are the babies God gave you, they deserve a chance at life.” “I knew someone who knew someone once who had the same situation; she didn’t reduce, and she was fine.”

I felt confused and hurt by the reactions: Was it possible to keep all three? Were the doctors lying to me, or not telling me everything? Did anyone actually think this was a choice I wanted to make? We questioned the doctors extensively, including about whether it was possible to reduce only one twin and keep the other, but no—the way our twins had developed, they would both pass.

Ultimately, I placed my faith in science and decided to reduce. Online support groups can be wonderful tools, or they can be toxic cesspools of judgment and advice from non-experts. I wouldn’t trust an accountant to fix my shower, so why would I trust an online group of people from various backgrounds on high-risk pregnancy questions? I wish these groups had been more supportive—it was a lonely and isolating experience without a group of people who had been through something similar.

Reducing a very wanted pregnancy

Multifetal reduction usually happens within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, but because the doctor we chose was very busy (being one of the most highly recommended doctors in the field), we had to wait until 13 weeks.

I felt powerless as the three fetuses continued to grow. I felt like a bad mother. I couldn’t get pregnant naturally, and, now, I couldn’t even hold a healthy pregnancy.

Again, I felt like I had failed.

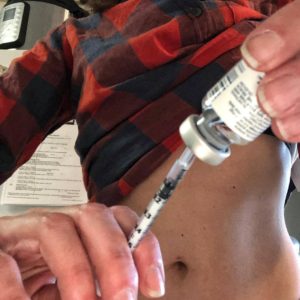

The day of the reduction, we had another ultrasound before the procedure, which showed us that one of the twins was still way behind, growth-wise. The doctor reconfirmed that twin would never make it, again quite possibly risking the other twin and the singleton. Using the ultrasound as a guide, the doctor inserted a needle containing potassium chloride through my belly into the placenta, stopping the twins’ hearts.

I cried. One, because it really hurt. Two, because two fetuses died in my womb. Two fetuses I badly wanted, did everything within my power to have, would have done anything for—gone, within seconds. We had gone through so much to have these babies, and, so quickly, they were gone.

The procedure cost us $14,000—another blow. We wanted babies. We had spent an astonishing almost $100,000 to get these babies. And now we had to pay for them to be reduced?

Life felt spectacularly unfair.

We were left with the singleton, a baby boy due in January. He is healthy. He is growing. I feel him kicking now, and I am so grateful to feel him dancing in my belly.

Sharing my story

Infertility itself is hugely stressful. I cannot remember feeling more exhausted, emotional, or hopeless. But since people widely don’t understand it, it’s hard to find support. There are no meal trains. There is rarely insurance coverage. There aren’t many people checking in.

But when you choose to reduce? Forget it. Many people were mortified I would even share the decision beyond immediate family. So many people go through infertility and/or multifetal reduction. Since sharing my story, I’ve received dozens of messages from people who have struggled—or are struggling—but haven’t talked about it publicly because they are afraid of what other people, who will never face these decisions, will say or think.

My journey to motherhood has been marked by grief, and I’ve continued to grieve throughout this process. I grieve for the losses and disappointments we, as members of this terrible, secret club, suffer. I grieve for those among us who endure in silence, without support, without community. It’s lonely. It’s isolating.

I grieve for the losses and disappointments we, as members of this terrible, secret club, suffer.

Until it doesn’t work, we think getting pregnant—and staying pregnant—will be magical and wonderful. This wasn’t the case for me, and it’s not for many: Approximately one in six couples struggle. My body became a science experiment. I didn’t feel well for years from the hormones and medications I had to take. We spent money we didn’t have, for children we weren’t sure we’d ever get—but we had to try. Month after month, and then year after year, passed, littered with hatefully red toilet paper and disappointment, and still we kept trying.

In the normal world, getting pregnant and having children is a joyful experience. In the world of infertility and multifetal reduction, we know that wonder and joy are our end goals—but to get there, we will walk through fire, pain, grief, loss, and, unfortunately, judgment.

But we are parents. And as parents everywhere know, we’ll do anything for our children.

Even if it means letting them go.

Like this piece? Subscribe to our newsletter for real stories about women on their journey to motherhood.